QRS has manufactured piano rolls at its home on Niagara Street in Buffalo since the 1960s. By the end of this year, they plan to close their doors for good. It’s the end of an era for player piano lovers. Former QRS Music Director Bob Berkman spoke with WBFO’s Nick Lippa about the company’s history and how his love for the instrument led to a lifelong career in Buffalo.

To play a player piano, start by putting your feet on the pedals, heels planted at the bottom, then pivot from your ankles. The harder you pump, the louder the sound from the piano.

“Part of the appeal of it, to me, is the utter magic of it,” said Berkman. “That this is a piece of paper with holes in it, and yet through the glory of gears and pumps and all the mechanism in there, it’s making music.”

Berkman joined QRS in 1975. At the time, he was an unhappy pre-dental student in Cleveland.

“I decided, ‘Well, I can do this extra-curricular thing and make a roll and go to Buffalo and I did all that and I showed my homemade roll to Ramsi Tick and he offered me a job. Here I am 50 years later. That was my career.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qh_R_GVJyM

The heyday of player pianos themselves was in the 1920s. During that time QRS was located in the Bronx. With the advent of radio and the depression, popularity for the instrument died off. After QRS’ owner passed away in 1961, Buffalo lawyer Ramsi Tick came in to the picture.

“Ramsi hated the practice of law. Didn’t want anything to do with it and had been managing the Buffalo Philharmonic. Music was really his first love and he also really enjoyed player pianos,” Berkman said. “He heard that this business was going to be up for sale. He went to the Bronx and served an apprenticeship there under the (deceased owner’s) widow and when she was ready to sell he bought it and moved it to Buffalo in 1966.”

But Buffalo’s history of player pianos starts earlier than the 1960s.

The Chase & Baker Piano Company was originally established in 1884 in Buffalo. They built upright pianos and player pianos until around 1910. Wurlitzer Piano was operating in North Tonawanda around that same time, and the Wood and Brooks Company moved to Tonawanda to open a plant to manufacture ivory keys and keyboards on Ontario Street. They slaughtered elephants to do so.

According to Berkman, in 1908 all these manufactures met in Buffalo and decided on the piano roll standards.

“There were several different formats. It was like VHS versus beta,” Berkman said. “In 1908 in Buffalo they decided, here’s what a piano roll is going to be. It’s going to be this wide and the holes will be spaced like this and the spools will have this configuration. That’s a feather in Buffalo’s cap in player piano history.”

QRS, which is the oldest piano roll company, was founded in 1900. Berkman said Tick bought the company at the right time.

“Suddenly there was a market for rolls (in the 1960s) and QRS was the only survivor from those days. So its business picked up considerably and Ramsi profited by that,” Berkman said. “But he was also a very innovative leader and did great things with QRS, and that’s where I enter.”

When Berkman arrived, the factory on Niagara Street was booming and employed 32 people.

“There was this glorious cacophony when you went in there. There was machinery running, perforators banging away. Rolls being tested, so there was piano music going on. And then there was arranging going on in the arranging room. So you would hear plinking and plunking and other machinery grinding and phones ringing,” Berkman said. “There was always the aroma of coffee. Coffee flowed through that place. There was a river of it. I was never a coffee drinker before I went to QRS and it just smelled so good I sort of eventually succumbed.”

While many who pursue piano rolls today may be viewed as collectors, this was not the case during the 1970s and 1980s.

“The people who were sustaining the piano roll business were not collectors. These were not people who dwelled on the past and loved the history and the finer points and this and that. They were just people who thought, ‘Oh a player piano what fun! And we can’t get these old songs and we can get these new songs.’ They were the ones buying roles and making the business possible. And Ramsi understood that. So instead of doing what collectors might have wanted, which was looking backward, Ramsi look forward,” Berkman said.

“He revived the hand-played roll. Rolls had been arranged since the early 1930’s. QRS had stopped making hand-played rolls, but under Ramsi’s leadership that was revived. And then he was able through his arts management skills to lure real talent. Liberace recorded rolls in Buffalo. George Shearing, Peter Nero, Roger Williams. He did a great job in building that up and in keeping current pop music available. That’s what we carried on even after he had sold it under the new management. We understood you can’t record the songs that you like. You have to record the songs that people are going to buy.”

In the 1970s, the only other original piano roll company that still survived from the heyday of players was The Mastertouch Piano Roll Company in Australia. Around this time a few other manufactures jumped in to the business.

One was the Aeolian company, which was originally founded in 1887 and made automatic organs originally. Then, Berkman said, there was a couple of hobbyist originated businesses.

“Some of them understood more than others about how to do it successfully. But QRS had such a big catalogue and so much momentum that they made inroads. It was a small pie and they took their little piece of it,” Berkman said.

QRS had the heritage other companies did not.

“The machinery was the same. The craft was the same. The master rolls had handwriting of artists from the 1920’s on them. There were labels on file from the days of Fats Waller and things like that. It was steeped in its tradition and the building on Niagara Street reflected that,” Berkman said.

Niagara Street had an industrial feel to it in the 1970s and Berkman said QRS fit in to that image.

“Rich Products was there and we were up the street from them. Real estate on Niagara Street was I think kind of in the doldrums, and now it’s hot,” Berkman said.

“When I was there it was the Broderick Park Inn, before it got renovated. Now it’s torn down. Before it was renovated, they actually had a player piano in it that I don’t believe even worked. But you’d go up to the bar and you’d order a liverwurst sandwich for 65 cents and it came in a little red and white checkered paper boat. That was Niagara Street in the 1970s,” Berkman laughed while reminiscing.

In the end, Berkman said he worked for 38 years for QRS with two years off for good behavior. He had left just before Tick sold QRS in the mid-1980s. Berkman ended up in New York working for IMG Artists, which also happened to have a Buffalo connection.

“One of the two founders of it was Charlie Hamlen, who passed away not long ago. He had taught French at Nichols and he went off to New York and ended up a partner in this great artist management firm,” Berkman said. “They managed Itzhak Perlman and Joshua Bell. So when I moved to New York, I, through Buffalo connections, got a job with IMG Artists, but then the new ownership of QRS made me an offer I couldn’t refuse and lured me back in. So here I am still.”

Dick Dolan was the new owner and had plans to update the QRS library. They took what was on a perforated roll and brought it to a more contemporary medium, now known as ‘Pianomation.’

“They wanted couch potato entertainment. The player piano was not that at least initially. It was very much a participatory thing. Even if you didn’t get deeply in to how to make it express by using the foot pedals and the hand controls which many people did not,” Berkman said. “All they wanted to do was tromp on the pedals and make the music come out. It was still participatory because the lyrics were printed on the roll and everybody would gather around the player piano and sing. So it was an involving way of making music. People I think they say, ’Oh yeah player piano those jangly things where you turn them on and they go.’ That’s only part of the story.”

Another large factor is a contemporary piano roll’s technology can better replicate what a human can do at the keyboard.

“Different notes are played harder and louder than other notes. The sustain pedal in subtle ways. The music has an expressive life to it. The player piano wouldn’t do that unless you knew how to make it do that and most people didn’t,” Berkman said.

INSIDE THE FACTORY

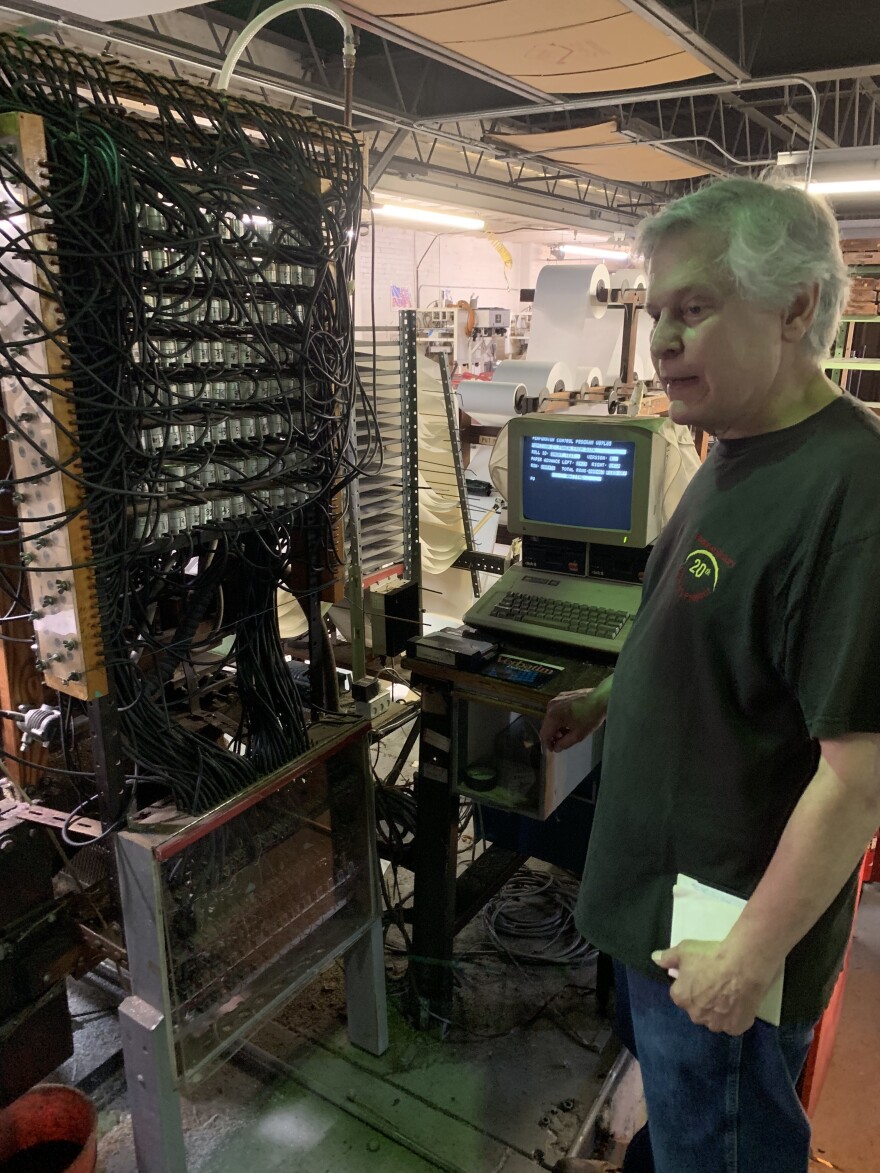

The perforator is where the process of manufacturing begins for a piano roll. In the '70s, all the information that was perforated was contained on a paper master roll that was read by another machine. That changed in the '80s.

“We converted to the Apple IIe computer. And that’s still how it’s being operated. So these little five-and-a-quarter inch floppies replaced the paper master roll.”

Berkman said the Apple IIe era is finally ending. They are changing to a laser system elsewhere.

“We were kind of late getting computerized. By the early '80s, a lot of things had already jumped on to the bandwagon. When we first got this up and running it was like, wowwww,” he said. “Especially in terms of arranging and editing it made things much easier and it also made the manufacturing easier. Paper master roles, as romantic as they may seem, they were kind of a pain in the butt. They would go off track. The sprocket holes that drove them would ware. They were far from trouble free. That Apple IIe may look primitive to you, but compared to the early 20th century technology of paper master roles, yes this was a quantum leap.”

Learning the science behind what makes a player piano roll never took away the magic they possessed for Berkman.

“Here we are in a plant where I learned exactly how that was done down to the molecular level. I’m very glad that I did and I understood it. But it doesn’t detract from the magic. It’s still a fascinating product and one that brought a lot of happiness to a lot of people,” said Berkman.

WHAT’S NEXT

QRS stopped regularly releasing rolls in the early 2000s. They’ve been doing one annual Christmas role since. When walking around the inside of the factory today, it looks trapped in time from a forgotten era. For Berkman that was part of the charm.

“What I enjoyed about it was the continuity. That when I worked here, all these machines and all these processes were pretty much the same as they had been since nearly the turn of the century,” he said.

“It was the workforce in Buffalo that partly made it possible. The pay was not fabulous, but you didn’t have to make a lot of money to live in Buffalo, New York to live in the 1970s or '80s or even the '90s. The living was easy here. And it made it possible for this place to survive,” Berkman said.

“It was a very delightful thing that Buffalo had here and I think Buffalo was part of it. We ran two shifts. We couldn’t make enough piano rolls.”

Berkman said he hasn’t been sad about it closing yet, but attributes some of that to being removed from the company for several years now.

“The Dolan leadership has moved QRS out of the 19th century and into the 21st. The 20th century, it never quite got out of the 19th. But now it’s in the 21st. The MIDI technology and whatever comes after MIDI, that’s the place to be certainly to have a going concern,” Berkman said. “And I was happy to be creating software for that system, but I was never affectionate about it as I am for this stuff.”

New player pianos can be operated digitally. But just like when you hear someone who prefers vinyl to a CD or download, Berkman just can’t quit the intimacy of an old fashioned player piano.

“It’s much more interesting to me to open it up and see the bellows going and knowing that this very old technology is creating something listenable and something that affects you. Something that can touch your soul from nothing more than a piece of paper with holes in it. I just think it’s the greatest invention of western technology. Well, maybe,” he laughed.